Keep up to date with the weekly Nestruck on Theatre newsletter. Sign up today.

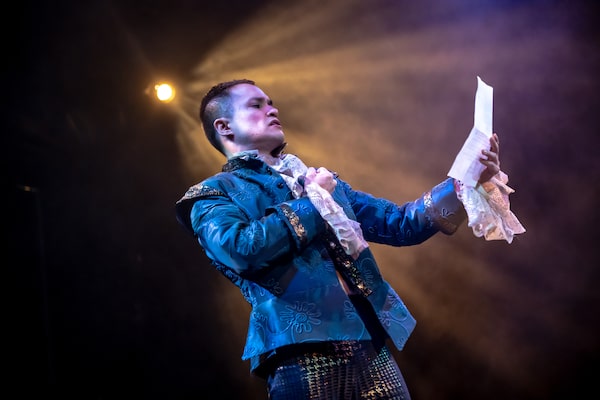

Karl Ang in Mad Madge.Handout

- Title: Mad Madge

- Written by: Rose Napoli

- Director: Andrea Donaldson

- Actors: Rose Napoli, Nancy Palk, Karl Ang

- Company: Nightwood Theatre in association with VideoCabaret

- Venue: The Theatre Centre (1115 Queen Street W.)

- City: Toronto

- Year: April 9–21, 2024

If well-behaved women seldom make history, what kind of women write it?

Lady Margaret Cavendish was one of few 17th-century women to make a name for herself in the literary world – and that’s just how she wanted it. Born into privilege, but having no formal education, Margaret wrote herself into the history books by cultivating a large literary oeuvre and a scandalous public persona at odds with a more bashful private self. She was the first woman invited to visit the scientific Royal Society, and her 1666 novel The Blazing World is considered by some to be the first science-fiction novel. Featuring herself as a major character, it’s considered by others to be the originator of the Mary Sue self-insert trope.

Playwright/star Rose Napoli and director Andrea Donaldson take on the legendary lady, who diarist Samuel Pepys once called “a mad, conceited, ridiculous woman,” in the Nightwood Theatre and VideoCabaret production of Mad Madge at the Theatre Centre. It’s a rollicking, no-holds-barred ahistorical romp that aims for a blazing world of glory, but one that’s paradoxically hampered by its devotion to a modern sensibility at all costs.

Napoli’s fast-paced script refuses the trappings of a typical historical biography, exploring Margaret’s desperate desire to be noticed in a world determined to deny her agency. The play echoes The Blazing World’s early example of metafiction, emphasized by its in-the-round setting and Madge’s use of direct address, assuring the audience that we will eventually catch up with her.

The central platform – a checkerboard of patterned red and blue panels by set designers Astrid Janson, Abby Esteireiro and Merle Harley – gets plenty of wear in its first act, which follows a young, socially inept Margaret leaving her overbearing family to serve as lady-in-waiting to the exiled Queen Henrietta Maria (a terrifically blunt Nancy Palk) in France after the beheading of King Charles I.

Izad Etemadi, Wayne Burns, Rose Napoli and Nancy Palk in Mad Madge.Handout

The two women form a friendship, drawing ire from two illiterate female servants (Wayne Burns and Izad Etemadi, doing their best drag Tweedledee and Tweedledum), and delight from William Cavendish (Karl Ang), a hunky-yet-sensitive gentleman who believes in the immortality of poetry and who tests Margaret’s desire to place self-determination over love.

From its first image – the titular woman defiantly wearing only pasties from the waist up before baring her equally naked ambition – Mad Madge delights in exposing a scatological sense of humour and its characters’ base desires. An elaborate royal commode, the bonding spot between Henrietta Maria and Margaret, gets plenty of onstage use.

The queen also finds release in increasingly wild sexual exploits, and everyone swears with relish and frequency when not using modern references such as “you no longer spark joy” or “nobody puts Baby in a corner.” While it’s a genuine gift to hear the regal Palk curse out Oliver Cromwell, this humour does have diminishing returns, especially once it’s no longer surprising.

Ang’s warm and gentle Cavendish – the one character outside of the striving, grasping chaos – is a soothing balm, providing some much-needed heart. While Mad Madge is very much a social commentary on fame and forgotten women, it’s also a romantic comedy. Perhaps ironically, given its lead character, that’s where it’s most charming and successful.

Like any proper period romance, the costumes also (designed by Janson, Esteireiro and Harley) are divine: rope-like wigs, rich fabrics and elaborate undergarments evoke the 1600s without claiming accuracy. Margaret cuts a fine figure in rakish leather breeches, and the hats she makes are much like herself, a mix of austere antlers and filmy chiffon. A second-act interview between Farhang Ghajar’s slimy host in a shiny brocade jacket and Napoli sporting a cloud of butterflies around her head evokes The Hunger Games’ Caesar Flickerman and Effie Trinket; of course, one could argue that they stole Madge’s look.

A sign outside describes the play as “not wholly inaccurate, but almost.” That Mad Madge plays fast and loose with the facts of Margaret’s life is liberating, but also frustrating. Because the truth is so opaque and malleable here, it’s hard to fully appreciate the impact of Margaret’s actual actions.

For example, it’s funny when Margaret’s visit to the stuffy Royal Society causes noted microbiologist Robert Hooke to wet himself, but it would be more meaningful if we knew for certain that Cavendish had published a brutal takedown of Hooke, the creator of the law of elasticity, that caused him to reach his elastic limit.

It feels as if the production doesn’t trust its audience to be interested if everything isn’t turned up to 11. At the same time, that’s exactly Margaret’s main complaint: Nobody’s going to listen unless you scream.

Mad Madge screams with the best of them. But it’s in the moments where Margaret quietly drops the persona to show the vulnerability behind her desperate need for love that the play fully connects. It’s in her “supernatural” affection for illegitimate brother Thomas, who admiringly calls her a “meteor.” It’s there when she reminds Henrietta Maria, demoted to Queen Mother status so her 11-year-old son can rule, that any power women has is transient. And it shines in her tentative, reluctant love story with Cavendish, himself a writer and the only person who loved her for her full self.

“I want to create my own world, then conquer it,” says a young Margaret. In Mad Madge, Napoli has certainly created and conquered a unique world – a world where nobody would dare put Maggie in a corner.